Six weeks, seven press conferences, and twenty-two front pages later, Reform UK’s Law and Order campaign wrapped up at the start of September. It was a textbook lesson in how to dominate the so-called ‘silly season’. While the rest of Westminster switched off – Labour’s frontbench included – Farage filled the vacuum with relentless anti-immigrant rhetoric.

Much of it was depressingly familiar: asylum seekers cast as economic opportunists, rule breakers, drains on public funds, even criminals. But this summer, something new emerged.

Small boats were said to be full of “fighting-age men” from “backward cultures,” who come to the UK to commit violent acts against women and girls. Unverified statistics linking Afghan men to gender-based violence were pushed out to reinforce the point.

And it worked. In early July, 50% of the public ranked immigration and asylum among the top three issues facing the country. By the end of August that figure had risen to 57%. To put that differently – that’s an extra 3,850,000 UK adults who were now saying that immigration and asylum was a top tier issue facing the country. For Reform, the campaign could hardly have been more successful.

Weaponising ‘protection’

At Unchecked UK, we have long known that ‘protection’ is a frame that cuts through – especially with socially conservative voters. Our early research with KSBR found the centre right voters are particularly animated by principles of fairness, discipline and enforcement — all of which can be expressed through a message about regulatory protection.

It’s why for many years we’ve argued that regulations should be presented as protections. Protecting children from harmful online content, workers from bosses that don’t play by the rules, consumers through high food standards, and communities through strong environmental laws that crack down on polluters. Protection is universal, relatable, and effective across issues.

Right-wing populism, by contrast, thrives on paranoia. It redirects real concerns about economic insecurity and social instability onto a single scapegoat: immigration. The message is simple, and the fear is easy to weaponise.

What’s new this summer is that Reform UK isn’t just stoking paranoia – they’re co-opting the protection frame itself. Much of their messaging has been directed through the lens of protecting women and girls. That isn’t accidental. At the 2024 election, Reform’s support skewed heavily male, leaving the largest gender gap of any political party. By portraying migration as a direct threat to women’s safety, they are using the protection frame not just to harden their base, but to broaden it.

But the narrative is hollow. While Farage talks about protecting the public, his party is working to dismantle genuine protections: opposing online safety rules to appease big tech interests, seeking to weaken environmental standards, promising to roll back reproductive rights for women, and – despite some recent pro-worker rhetoric – voting against the Employment Rights Bill at first reading.

These are the protections that genuinely keep families and communities safe. In their place, Reform offers only manufactured fear designed to distract from the real challenges people face.

Reform UK’s new media ecosystem

Reform’s protection narrative had significant cut through over summer as the far right mobilised outside migrant hotels and editors plastered Farage’s image across their front pages. But Reform’s success isn’t just about finding the right words – it also reflects their evolving skill in political communication.

Alongside their shiny new in-house studio in Millbank Tower, London, they’ve built a friendly press and broadcast ecosystem around them. GB News – effectively a Reform propaganda outlet with Farage fronting a weekly show – overtook both the BBC and Sky News in July viewing figures. Alongside Talk TV, Reform UK can now harness very sympathetic broadcast channels to push their message.

More neutral broadcasters like Sky News have even got into hot water for providing excessive coverage to Farage. In August, the broadcaster interrupted footage of the Lionesses victory parade to cover a Reform UK press conference. At times this summer, it has seemed Farage needed only to sneeze for a camera to be trained on him.

A similar dynamic is playing out in the mainstream Tory press. Although Reform UK had no official press endorsements at the 2024 General Election, they can increasingly count on a wave of friendly coverage from traditionally pro-Tory papers. The party enjoyed as many as 22 front pages over the summer alongside a string of op-eds in The Express and The Mail, double page splashes in The Sun, glossy coverage in The Times, and constant amplification of the campaign in The Telegraph. The tectonic plates of Conservative media alliances certainly seem to be shifting, and Reform HQ could hardly be happier.

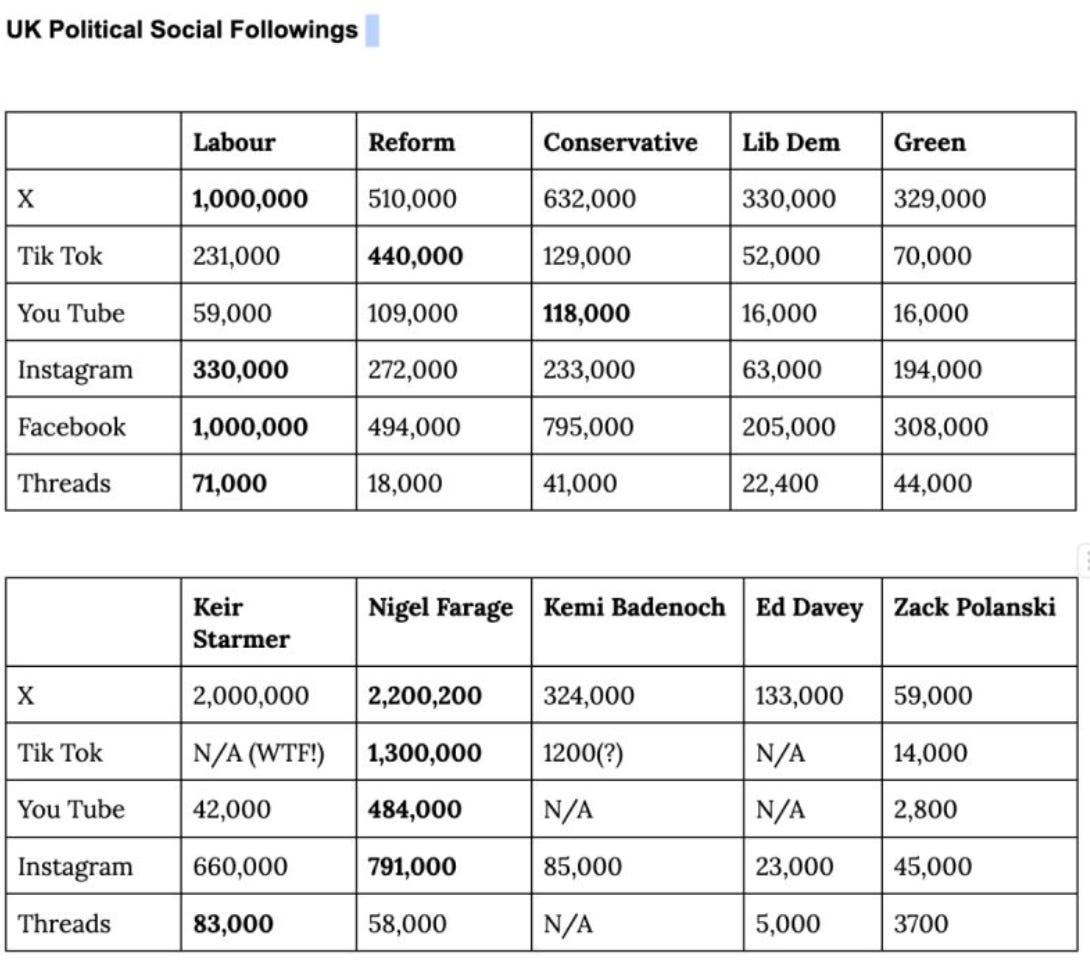

But it’s not just traditional platforms which Reform UK is now able to rely on. Farage himself has built a formidable and ever growing social media empire. The Reform UK leader has amassed more TikTok followers (1.3 million) than all other MPs combined. Kier Starmer isn’t even on the platform. Farage also has far more followers on X and Instagram than almost any other leader of a political party – although Starmer is a close second on some platforms.

Farage was able to use this social media empire to great effect over summer. As Inigo Conolly’s research found, on TikTok, his most popular video over the summer generated 1.7m likes – more engagement than the UK’s most read daily newspaper, The Metro, which has a daily circulation of just under a million. On X, his top campaign post was viewed 5.7m times and his second place post was viewed over 2m times.

With over half of under 34’s now saying that social media is their main source of news, Farage’s social media empire is providing unparalleled access to audiences well beyond the party’s traditional, older base.

Reclaiming ‘protection’

What can progressives do to combat this? If we retreat from ‘protection’, we allow rightwing populists to monopolise a deeply resonant frame. As living standards continue to stagnate, public services struggle with underfunding, the climate crisis intensifies, and international conflicts proliferate, safety rhetoric is only going to become more persuasive. The more Farage is able to redirect this fear and uncertainty towards immigration, the more the ‘strongman’ appeal of authoritarianism grows.

That’s why we can’t afford to abandon the protection frame. Instead, we must reclaim, and broaden it. We need to show that protection isn’t about shutting borders; it’s about safe workplaces, safe streets, safe homes and a safe planet.

To reclaim it, progressives need to do two things. First, expose the hollowness of Reform’s message – highlighting the contradiction of a party that rails against asylum seekers crossing borders while enabling the super-rich to dodge taxes and stay above the law. Second, show how tools like regulation can deliver the everyday protection that people actually rely on: whether that’s ULEZ zones that make communities healthier, food standards laws that prevent deaths, or workplace regulations that ground wealth in local communities.

But this is not just about the message – it’s about the medium. We need to meet Reform UK in the media ecosystem they are building: TikTok, short-form video, reactive content. Progressives are on the backfoot here and struggling to keep up in a rapidly changing media climate that is geared towards the sensationalist messages Farage thrives on. If we fail to contest online spaces, we concede whole audiences to right-wing populists.

Interesting work is being done to explore how we can adapt to new digital information ecosystems. And progressive politicians are already having a good degree of success with new forms of digital communication.

Across the pond, Mamdani was able to win a significant victory with a simple message about fairness, executed through well produced, yet simple videos. Zack Polanski followed a similar path and recently won The Green Party leadership race by a convincing margin. And inside the Labour party, young MPs are leading the way with a new brand of digital comms that is beginning to challenge the right’s online dominance.

These efforts show how progressives can compete with a message rooted not in fear, paranoia, or scapegoating, but in fairness, dignity, and genuine protection. We can and must learn from these examples. If we fail to do so, we leave the door open for the populist right to surge through.